About Handspun | About Ikat

About Handspun

Handspun and handwoven is so much more than simply a beautiful type of fabric. It is an idea of cultural self-sufficiency with deep roots in the Indian identity.

In its essence, handspun threads and handwoven fabric are created through personal labour without industrial machinery. Handspun and handwoven thus harkens back to the centuries when India produced the world's most prestigious cloth. But with it’s emphasis on manual skills and hand production, handspun and handwoven also had a central role to play in countering the displacement of family life that took place during industrialization.

Within Great Britain, industrialization produced tensions between textile workers and mill owners. The luddite riots against mechanized forms of spinning, weaving, and knitting are today largely remembered for adding the word we use to depreciate ourselves whenever we fail to work one of our gadgets. The unrest was real, however, and troops were mobilized to put down the mobs. With the riots quelled and resistance to industrialization largely subdued, British mills were soon tooling up in an effort to break into one of the largest markets on earth – the Indian textile market.

As an anti-industrial movement, the luddite riots (and later Swing riots against threshing machinery) were relatively small and did not divide the country. Within India, by contrast, anti-colonialism and anti-industrialism were perceived as synonymous. In what must have been one of the largest market takeovers in history, cloth for the Indian market was no longer being woven by artisans living in the subcontinent; instead, India exported raw cotton to England, where it was transformed into thread and cloth and sold back to the Indian public. As in England, Indian cottage industries and village-producers could not compete with industrial capacity.

An early and articulate cultural critic of industrialization is John Ruskin. In The Stones of Venice Ruskin argues that it is the craftsperson who should be accorded a creative position in modern society. Industrial virtues such as uniformity of multiples are not virtues he argues, but defects. Ruskin’s first rule to empower craftspeople is the awkwardly worded: “Never encourage the manufacture of any article not absolutely necessary, in the production of which Invention has no share.” Although Ruskin had Venetian stone masons and glassblowers in mind, this sentiment could be applied to almost all Indian crafts.

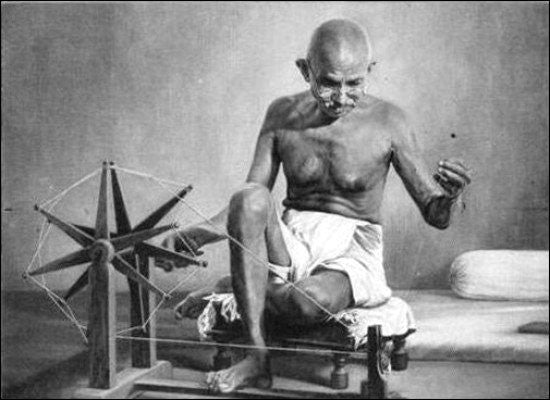

What might happen if Ruskin’s ideas championing the artisan-producer were translated into the Indian context? Mahatma Gandhi had the ideological conviction and motivation to find out. In 1908 Gandhi translated Ruskin in to Gujarati. He chose a latter work with more emphasis on social economics and morality and less emphasis on aesthetics:

‘Unto This Last’, I translated it later into Gujarati entitling it ‘Sarvodaya’ (the welfare of all). I believe that I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book of Ruskin and that is why it so captured me and made me transform my life. — Mahatma Gandhi.

Gandhi’s exhortation to boycott British imports and mill-made fabric, and for everyone to spin and weave their own cloth is now well known. The effect of the Swadeshi (homerule) movement was to slow the erosion of traditional Indian hand production—especially weaving.

Traditional handloom is a remarkably flexible technology. Its great advantage lies in the production of embellished fabrics (supplemental wefts, jamdani’s, single and double ikats) and weaves of extraordinary fineness such as muslins. Because the operator has control over each throw of the shuttle, continual fine adjustments can be made as the cloth is woven. The weaver can also start and stop as each thread is adjusted or supplements are added. The mechanism of the loom–almost always worked with bare feet–permits the weaver to judge by feel when it is too damp, or too dry to continue working with extremely fragile fine-spun cotton.

Handspun threads and handwoven fabrics may be made from any fibres, but the term usually indicates cotton.

Portions of this text were first published in Tim McLaughlin's essay which appeared in V&A Magazine #38 - Winter 2015.

About Ikat

IKAT - Weaving with resist-dyed threads.

There are many ways to pattern fabric. One of the most intricate and time consuming is to dye the actual yarns first - before they are woven into cloth. It is a design technique that appeals to the calculating mind, as all the threads need to be kept in perfect order so that the final pattern appears in registration as the cloth is woven.

The simplest ikat is warp ikat; where the threads running the length of the cloth are bound together so tightly that the dye cannot penetrate. In central India, old bicycle inner tubes are cut into strips and these are used to tie the hanks of threads. It is a tie-and-die process worked on the threads.

More complicated is weft ikat, where the threads that run the width of a cloth are dyed. This process requires special weft racks which the ikat artisan use to measure threads to match the width of the cloth. They are then tied and dyed. Each throw of the shuttle (every single thread running width-wise) must be adjusted as the weaver progresses. A little slippage at the beginning will influence all future threads.

The most complicated ikat cloth is double ikat. Here both warp and weft threads are tied to resist the dye and both sets of threads must be kept in perfect alignment to keep the pattern clear.

If this all seems complex, remember that preparing the threads to resist the dye must be done for each colour. The artisan must tie, dye, and then untie the resist bands for each colour. The artisan works in reverse, resisting the area that the dye will not appear. If the artisan is building up colour combinations, they also have to imagine the blending of overdyes as they calculate their resist.

Traditional ikat artisans don’t consider this odd, or even overly labour intensive. Indian artisans have woven patterned ikat for centuries. Each village, and each district has a repertoire of ikat patterns and designs. Some are a simple as a white motif on a single coloured ground. The most complex are worked in fine silk threads in multiple colours. These complex double silk ikats are some of the most prestigious cloths that the world has ever known.